Racquet mass profiles

A work in progress.

One of the posters on the Talk Tennis bulletin board (the fora generously provided by Tennis Warehouse), made a great deal of explaining racquet differences in part by stating that such and such a racquet had more mass at the bottom of the hoop, and that other racquets had concentrations of mass elsewhere. These comments seemed very odd to me, not the least because I doubted that the poster had any idea what he was talking about, and also because it seemed that the only way to know about concentrations of mass in a racquet would be to section the racquet and weigh each piece — a procedure that would require sectioning at least two of each racquet, to avoid missed data points due to the mass lost in the sectioning process.

I wasn’t about to start sectioning racquets, but it got me thinking that it might be possible, using published racquet specifications and a little math, to reveal where in the racquet the mass is concentrated, if anywhere.

Therefore, I started playing around with the parallel axis theorem, hoping that by applying the theorem to racquets of known specifications, I could create racquet profiles,

which would shed some light on the mass distribution throughout the frame of the racquet. I believe I have successfully applied the theorem, but I’m not certain that I understand everything I know about the results.

For those who want to work through the math themselves, I used as the equation:

\[Ia = I_{10} + M \times [2 \times(10 - a) \times r - (10 - a)^2]\]

Ia is the swing weight at distance A from the butt cap, I10 is the published swing weight (at 10 cm up from the butt cap), M is the mass of the racquet, a is the distance from the butt cap to the new axis of rotation, and r is the distance from the mass center (AKA balance point) to the new axis of rotation.

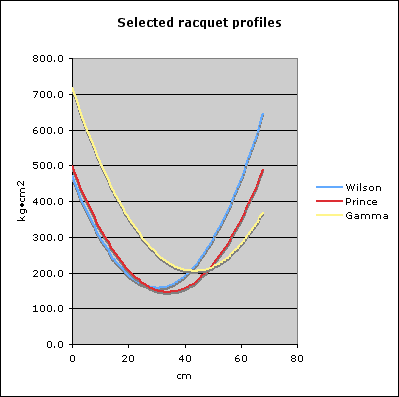

For purposes of illustration, I used three racquets, a Wilson, a Prince, and a Gamma; the Wilson because it has the lowest published balance point, the Prince because it is almost evenly balanced, and the Gamma because it has the highest published balance point.

| Wilson | Prince | Gamma | units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | 340 | 299 | 270 | gm |

| Balance point | 30.25 | 34.25 | 43.5 | cm |

| Swing weight | 297 | 322 | 508 | at 10 cm |

| Racquet length | 68.58 | 68.58 | 81.28 | cm |

Because lines and lines of numeral calculation results can be difficult to visualize, I created a chart of the results.

The lines on this chart may seem a bit counter-intuitive. Where the lines start on the left is the calculated swing weight if you could swing the racquet by the end of the butt cap, so what you’re really seeing is the weight of the head of the racquet (because it is farthest away from the axis of rotation). At the right end of the chart, the lines represent what it would be like to swing the racquet grasping it by the head, so you’re really seeing the weight of the handle. Toward the middle of each line, the low point represents the mass center of the racquet. (Note: The last data point shown for each racquet is at 68 centimeters.)

The Wilson — being head light — swings heavier

from the hoop than from the handle. The Prince swings about the same from either end, by virtue of its even balance. The Gamma swings much heavier from the handle than from the hoop, because the mass is biased so much toward the tip of the racquet.

However, I’m not certain where to go from here. The curves are smooth and continuous, without lumps (as far as I can see), so if there are any concentrations of mass other than the obvious ones (head-light, head-heavy, etc.), I’m not seeing them.

Furthermore, I’m wondering if this is a valid approach. Given a hypothetical racquet with a concentration of mass at the bottom of the hoop, this mass would pull

the balance point toward it, which would affect each of the calculations in such a way as to essentially hide the concentration from this type of analysis.

On the other hand, comparing — say — the ratio of the balance point to the swing weight might reveal something, but it wouldn’t tell you the location of any concentration of mass.

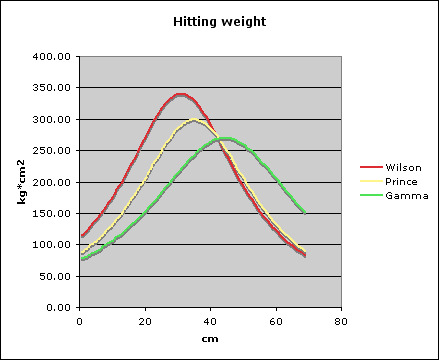

After putting my questions to the posters on the Tennis Warehouse message board, one suggestion that came back was (if I understood it correctly) to map hitting weight against racquet length. This involves a bit more math, but here are the results:

Although this chart is easier to read, it appears to me to be essentially similar to the previous chart, where the peak is at the balance point — no surprise there.

One other suggestion, which I myself had thought of after posting my query on Talk Tennis, was to take a known racquet and add mass along the length and redo the measurements. This sounds like a good idea, and one I’ll do ASAP, but at this juncture it’s difficult to see how these mathematical approaches will reveal the location at which the mass is added. We’ll see.

Addendum: Jun Wong from New York points out that you can obtain the volume of some segment by using the Archimedes principal … dipping in water and measuring the amount of water displaced.

Brilliant, but it sounds as if this would involve a lot of work. The point of this exercise was to see if one could calculate the mass profile of a racquet — that is, using math alone rather than actually doing measurements. If you have (or develop) the means to measure the racquet mass profile, then you certainly do not need to bother yourself with any of the above bloviation.